Discover Modernism in Connecticut: A Three-Day Driving Tour

Think Connecticut, and the mind conjures up clapboard houses and picket fences. However, architecture enthusiasts know the state for its glass walls, cement, and dark wood—the signature materials of Modernist architects who once transformed the landscape.

Connecticut Modernism began to take shape in the 1930s when Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus design school, fled Germany and took a position at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. His associate Marcel Breuer soon joined him, and together they mentored a generation of architects that included Modernist icons Landis Gores, John M. Johansen, Eliot Noyes, and Philip Johnson.

Subsequently, in the 1940s, many of these pioneers established firms in Manhattan while also purchasing homes in Connecticut. Buoyed by the post-war boom, vibrant towns like New Canaan and Stamford became creative hubs filled with boldly designed residences, churches, and schools. By the 1960s, as urban redevelopment swept the nation, Modernist office buildings began to appear. Today, several of the finest examples of this architectural era are concentrated between Stamford and Hartford, making them ideal for a three-day driving tour.

Day 1: Modern New Canaan

11 a.m.: Begin your journey in New Canaan, home of the famed Harvard Five—Breuer, Gores, Johansen, Noyes, and Johnson. The town is famous for Johnson’s iconic Glass House (open May–November; tours from $25). This extraordinary glass box, measuring 1,800 square feet, stands in a picturesque meadow and features Mies van der Rohe Barcelona furniture alongside a central brick core housing the fireplace and bathroom. The grounds comprise additional structures—a studio, a pond pavilion, and a sculpture gallery—while offering breathtaking views of lush greenery from inside the house.

2 p.m.: The highlight of nearby Irwin Park is the 1960 Gores Pavilion (open May–October), a former pool house boasting floor-to-ceiling windows, a cantilevered roof, and a notable Prairie-style fireplace, reminiscent of Frank Lloyd Wright. Preservationists saved this gem from demolition in 2005, ensuring it remains fully restored and furnished with couches by respected designer Jens Risom.

3 p.m.: While it may not adhere strictly to Modernist design, Grace Farms, a nonprofit community and spiritual center set on an 80-acre preserve, is an essential stop in New Canaan’s architectural journey. The site features River, a winding structure designed by Pritzker Prize-winning Japanese firm SANAA, featuring a sloped roof interconnecting breezeways and interiors. Nearby, you’ll find the Eliot Noyes House, characterized by two glass wings that flank a lush courtyard, which—though not typically open to the public—can be accessed during special tours hosted by the Glass House or local historical society.

6 p.m.: Conclude your day in the picturesque Silvermine area of Norwalk at GrayBarns (doubles from $500). Following extensive renovation, this 19th-century building has transformed into a stylish boutique hotel and restaurant.

Day 2: Churches and Cityscapes

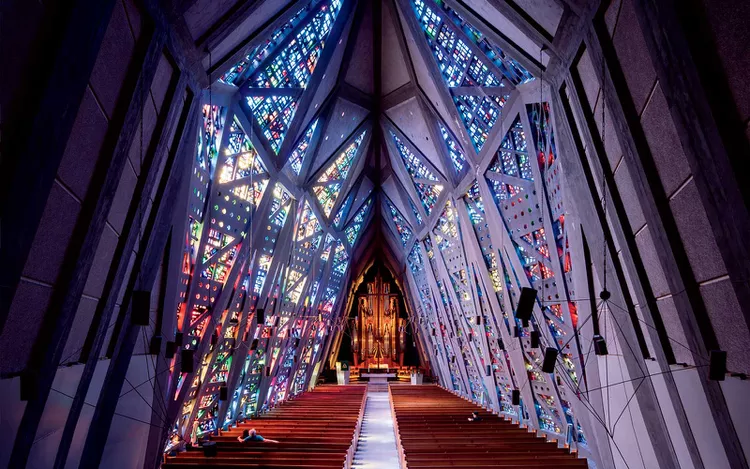

10 a.m.: Connecticut’s mid-century architects envisioned numerous spectacular churches, with Stamford’s First Presbyterian, created by Wallace Harrison—who later designed New York’s Metropolitan Opera House—topping the list. Dubbed “the Fish Church” for its fish-like shape, this structure features deeply saturated French dalle de verre stained glass—the first used in America. The glowing interior, illuminated by minimalist chandeliers, resembles the center of a giant sapphire.

11:30 a.m.: On a hilltop in Westport, the Unitarian Church provides a serene experience. Designed by Victor Lundy in 1959, it was inspired by a pair of hands in prayer, featuring a curved wooden roof divided by a skylight. Through the chapel’s glass walls, attendees can admire a grove of elms and evergreens.

3 p.m.: Proceed to Hartford to witness some of America’s first Bauhaus-inspired interiors at the Austin House, part of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art (tours three times a month, $25). Long before the Harvard Five made their impact, A. Everett “Chick” Austin Jr.—the museum’s director—fostered a love for Modernism in the city. The first floor of his 1930 neo-Palladian mansion boasts Baroque-style decor reminiscent of an 18th-century parlor, while the upstairs features a dramatically different aesthetic, with a dressing room designed by Gropius showcasing stainless steel finishes and Breuer furniture.

5 p.m.: Check into the Goodwin (doubles from $249), a boutique hotel housed in an ornate 1881 building, recently reopened after a major renovation. A stroll eastward will lead you to witness the sunset over the 1963 Phoenix Life Insurance Co. Building (1 American Row), celebrated as the world’s first office building with dual lateral façades, designed by Harrison’s business partner Max Abramovitz.

Day 3: New Haven, Beyond the Campus

11 a.m.: The Yale University campus is replete with Modernist buildings created by former faculty members and students, including Eero Saarinen’s Ingalls Rink (73 Sachem St.), known for its unique, undulating roof affectionately dubbed “the Whale,” along with Louis Kahn’s Yale Art Gallery and Center for British Art. However, the surrounding town also deserves exploration. Near the junction of I-91 and I-95 stands Breuer’s 1968 Armstrong Rubber Co. Building—a haunting example of his Brutalist style, currently partially demolished yet striking, situated in a parking lot of an IKEA. Recently, the first floor opened for a site-specific art installation, Tom Burr/New Haven (by appointment only). Burr, who grew up nearby, had always been captivated by this space, and his conceptual piece—intertwining salvaged materials from the building and elements highlighting New Haven’s history of political activism—provides a unique glimpse into its rugged interiors.

12:30 p.m.: Before departing the area, visit another Brutalist landmark, the Johansen-designed Dixwell Avenue Congregational United Church of Christ (217 Dixwell Ave.), situated just north of the campus. Though founded in 1820 by former slaves and distinguished as the world’s oldest African American UCC church, the current building dates from 1967, showcasing vertical cut-stone slabs and a two-story central tower. This impressive structure illustrates the evolution of streamlined styles introduced by European refugees into a bold, distinctly American architecture.