The Writer and the World

The best voices in travel writing, from pioneering female reporters and Black novelists to immigrant authors, have always documented the globe with clear eyes—and their perspectives are more relevant than ever.

Aldous Huxley’s Journey

In 1925, Aldous Huxley set off on a journey around the world to collect material for his travelogue Jesting Pilate. Huxley, though only 31 and not yet the author of Brave New World, was already a literary star in London. Upon arriving in India, he was invited to a tea party by Sarojini Naidu, an eminent politician. A young Muslim man rose and recited some verses by the Urdu-language poet and philosopher Muhammad Iqbal, the subject of which was Sicily. It was “a Mohammedan’s indignant lament,” Huxley wrote, “that the island which had once belonged to the Musulmans should now be in the hands of the infidels.”

Realizing the implications of this poetry, Huxley felt some indignation of his own. “For us good Europeans,” he wrote, “Sicily is Greek, is Latin, is Christian. The Arab occupation is an interlude, an irrelevance.” It was unreasonable, in his view, to represent a place he considered to be “classical ground” as “a piece of unredeemed Araby.”

However, mid-indignation, Huxley shifted his tone from strident to reflective. He soon recognized that the act of seeing and being seen, of contesting narratives describing the same place, is critical to the essence of travel. “In the traveler’s life,” Huxley stated, “these little lessons in the theory of relativity are daily events.”

Reexamining History

The sense of affront Huxley experienced that day in Mumbai resonates with our contemporary reckoning. From Seattle to Brussels, statues are being dismantled, reflecting a deep reassessment of historic narratives that often celebrate figures linked to racism and colonialism. History, with a capital H, is alive and demanding attention.

Across the globe, established narratives about our past are being challenged, compelling us to reevaluate which voices we honor in literature and media. Many questions arise: Which authors have we favored, and which have we overlooked? Do those we revere share our backgrounds? Have certain demographics been disproportionately represented while others have been marginalized? Huxley had to travel to India to confront the discomfort of having his deepest values challenged, and today, as we reconsider history in the West, that discomfort is manifesting within our own borders.

The Role of the Outsider in Travel Writing

Throughout my life, I have been deeply aware of the outsider’s role in travel writing. Growing up gay and of mixed heritage (half Indian, half Pakistani) in New Delhi, my perspective was never singular. Additionally, my marriage to someone from Tennessee, of an evangelical Christian background, has further broadened my understanding of diverse viewpoints.

This perspective is familiar to a group of travel writers I often categorize as “outsiders.” These authors, hindered by societal constructs such as race, gender, sexual orientation, or class, cannot travel as if the world entirely belongs to them. Consequently, they tend to observe with clearer eyes, refraining from imposing their worldview onto those they encounter.

V.S. Naipaul’s Unique Perspective

One such compelling figure is the late V.S. Naipaul, who served as a mentor in my writing journey. Naipaul came from a lineage of Indians sent to the Caribbean as indentured laborers by the British post-abolition. Unlike Huxley, who represented the upper-middle-class perspective of a colonial empire, Naipaul embodied the quintessential outsider.

In his 1990 book, India: A Million Mutinies Now, Naipaul articulates awakening to history—a concept that poignantly encapsulates our current societal moment. “To awaken to history,” he noted, “was to cease to live instinctively. It was to begin to see oneself and one’s group the way the outside world saw one; and it was to know a kind of rage.”

Voices Silenced by History

This desire to restore voices to those muted by historical narratives has led to a new wave of literature. For instance, in 2013, Kamel Daoud’s novel, The Meursault Investigation, retold Albert Camus’ The Stranger through the eyes of the murdered Algerian’s brother. Daoud’s work addresses historical muteness, striving to portray the untold side of the narrative.

As individuals lacking a singular culture or literary canon, finding literary voices that resonate becomes paramount. Personally, I sought representation in writers like Arthur Koestler—a Hungarian Jew exiled across Europe before settling in England—and Octavio Paz, the Mexican diplomat and Nobel Prize-winning poet, whose works about New Delhi resonate deeply.

Understanding Our Collective History

Both Paz and Koestler share a unique outsider perspective, steering clear from speaking from positions of power or cultural dominance. Their unconventional angles enhance their work, creating profound literary connections.

Upon relocating to the United States, I sensed an impatience toward its historical context—a belief that this nation was somehow exempt from its past. Paz astutely stated, “the future to be realized, implies a critique of the past,” suggesting that the U.S. had a different relationship with history, one often suppressed or avoided.

The Pain of History

Today, America’s history is surfacing in undeniable ways, forcing a national introspection. The reluctance to confront painful narratives has come under scrutiny. This was supported by Rebecca West, an Englishwoman covering the Nuremberg Trials, who reflected on the complexities of American identity at a time dominated by male authors. One interaction she witnessed encapsulated this tension:

A newspaper owner, dismissively asserting America’s lack of historical baggage, was met with the probing observation that such issues existed “like the rest of us.” This moment highlights that, indeed, we are all shaped by the laws of history.

The Function of the Outsider

Writers embodying the “outsider” perspective perform an essential role in challenging and questioning societal norms. The dominant narratives of any culture are rarely free of bias. Examining our shared truths through the lens of outsiders invites reflection and often provocation, pushing against entrenched beliefs.

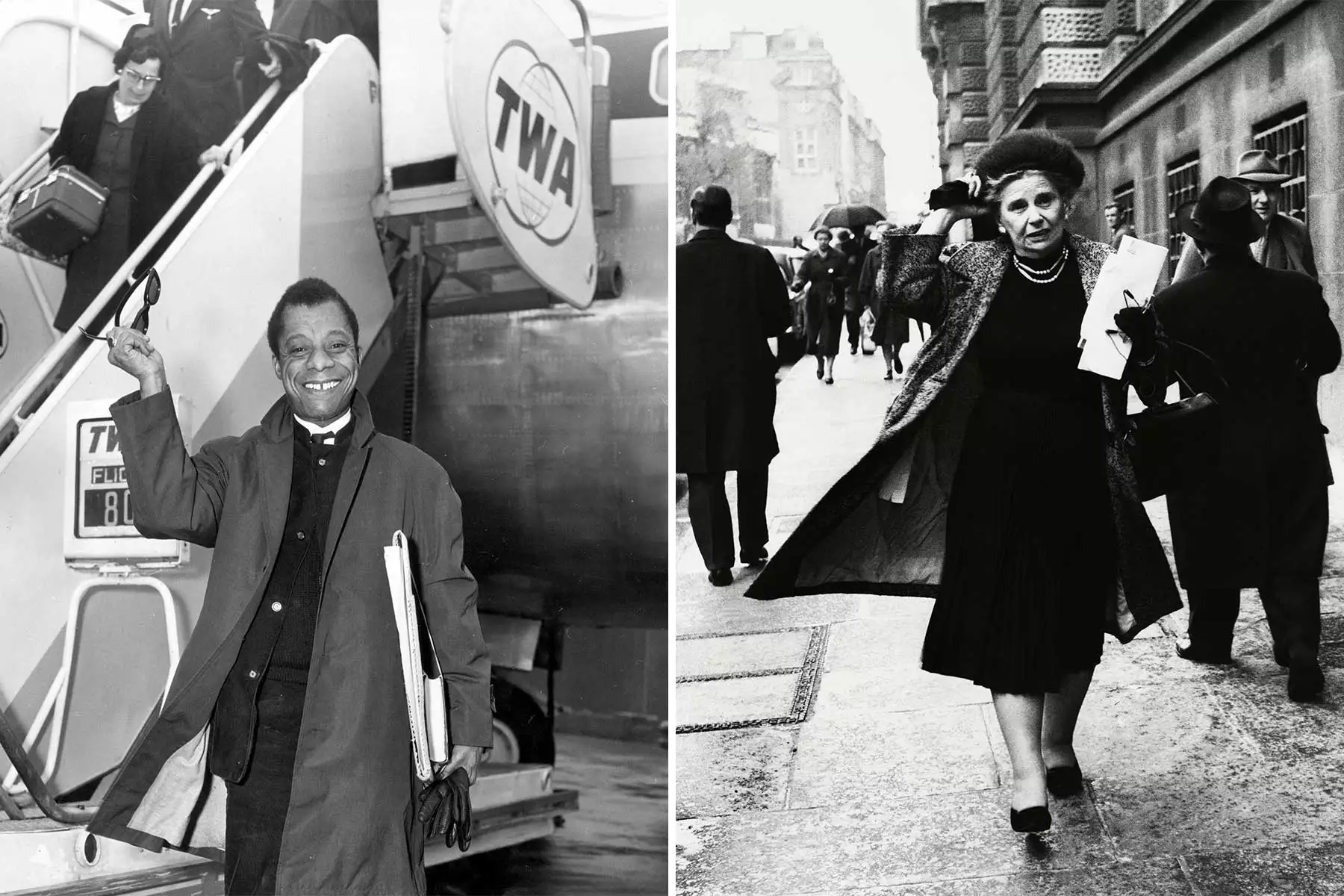

James Baldwin’s Powerful Insight

James Baldwin’s essay, “Stranger in the Village,” exemplifies this concept. In his account of arriving at a Swiss village where locals had never seen a Black man, he capitalized on isolation to portray the dynamics of race relations in America. Baldwin grasped that “People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them,” signaling a deeper, unresolved historical consciousness.

Through such reflections, it’s imperative to understand how we appear to those unfamiliar with our lived experiences. As Baldwin wisely noted, “Not everything that is faced can be changed; but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

A version of this story first appeared in the October 2020 issue of iBestTravel under the headline The Writer and the World.