Summary

Most visit Joshua Tree National Park for its yucca-dotted desert beauty, with hiking trails and boardwalks to see these spiny tree-shaped plants up close.

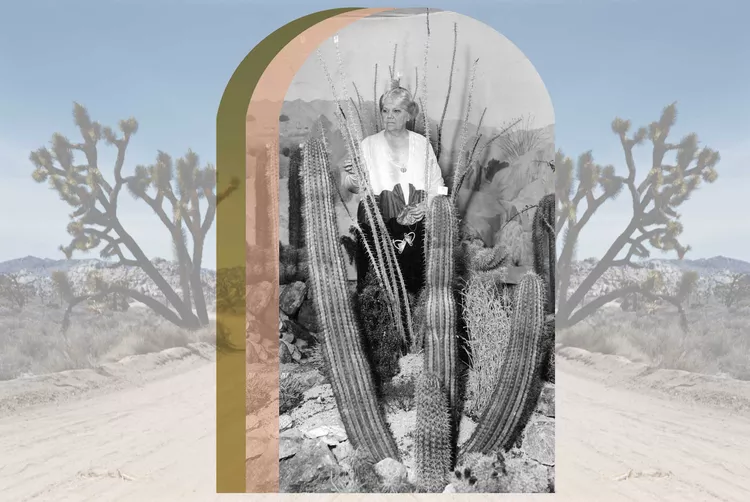

However, this vast swath of California desert does more than dazzle visitors; it holds the story of one of the state’s most integral yet oft-overlooked conservationists, Minerva Hamilton Hoyt. In fact, Hoyt is largely the reason this protected stretch of yuccas exists to this day.

Who is Minerva Hamilton Hoyt?

Hoyt wasn’t born with a love for California deserts. She grew up in Mississippi and later moved with her husband to New York City and then to South Pasadena in 1897. The latter is where her passion for the land took root.

“Her interest in desert plants grew into a passion for desert conservation and helping people understand the importance of desert ecosystems,” said Joe Zarki, author of the 2015 book “Joshua Tree National Park” and vice president of the Joshua Tree National Park Association.

The Top 25 National Parks in America

After Hoyt’s husband passed away in 1918, she devoted her life to desert protection. Consequently, she became synonymous with desert conservation. In the 1920s, renowned landscape architect and wildlife conservationist Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. sought her help with surveying land for California’s first state park system.

“A goal of the effort was to identify the best localities to protect Joshua Tree,” said Zarki. “Hoyt favored the stands of Joshua Tree among the scenic granite boulders of the Little San Bernardino Mountains (north of Palm Springs) as one area for state park preservation.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/minerva-hoyt-mural-joshua-tree-MINNIEHOYT0322-d4f17f4db9054ab68e763ae248883d94.jpg)

Creating Parks in California’s Desert

Initially, Hoyt had recommended this portion of the yucca-dotted desert for state park status. By 1930, she realized national park status would lead to greater protection. Thus, Hoyt hired biologists and ecologists to help solidify her case.

“She recognized that people would only preserve the desert if they had a better understanding and appreciation of its values,” said Zarki. “Many people at the time thought deserts were valueless wastelands that merited no protection at all.”

That hardly stopped Hoyt. Consequently, she continued her work until higher-ups, including President Franklin Roosevelt, took notice, ultimately establishing Joshua Tree National Monument in 1936.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Paavonpera_TL_California_Joshua_Tree_21-198c5dbcdca6430599e5ff35ecf55853.jpg)

The Road to National Park Protection

Hoyt recognized that national monument status was a good first step, but it wasn’t sufficient to protect the area from external threats like mining.

“Even after the creation of the national monument, its fate was not secure,” said Zarki. “Hoyt continued to fight for protection of the area from threats posed by mining interests and land developers.”

Moreover, Hoyt rallied for national park protection until her death in 1945—and she was not crying wolf. Even as a national monument, Joshua Tree saw nearly 290,000 acres removed for mining projects in the 1950s.

Fortunately, Hoyt’s decades-long fight for the California desert paid off. In 1994, Joshua Tree became an official national park, restoring nearly all of those 290,000 acres as part of its status. Additionally, in the 1980s, the United Nations recognized this diverse transition area between the Mojave and Colorado deserts as a Biosphere Reserve, which includes Joshua Tree and Death Valley national parks.

“The long, sometimes lonely, efforts of [Hoyt] to achieve her dream have a heroic quality that is inspiring to this day,” said Zarki. “What she achieved as a widowed female trying to persuade a world dominated by men should be an inspiration to women everywhere.”