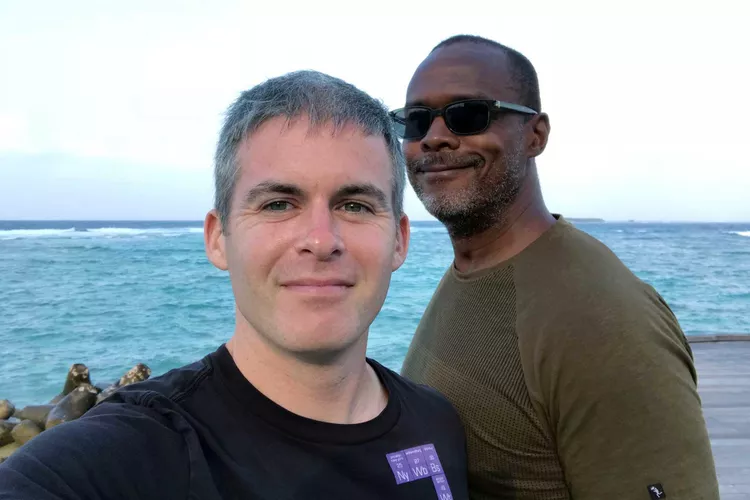

LGBTQ travelers are venturing around the world, whether the world is ready or not. A writer and his husband receive warm welcomes — and a little comical confusion — in unlikely destinations.

My husband and I, undaunted by whatever dangers might face a gay interracial couple abroad, have traveled fearlessly enough to frighten my in-laws. The Philippines. Cape Verde. Vanuatu. Colombia. We won’t go to Brunei, though. We disapprove of countries where it’s legal to stone gay people to death. In fact, we disapprove of stoning people to death in general. And not just because it’s messy. Brendan and I don’t want to support the economies of places with homophobic laws, like Myanmar, Kenya, or Saudi Arabia — the latter’s royal family hardly needs our three-dollar bills.

We did go to the Maldives, where they have whipped people for homosexual activity, but there seem to be separate rules for locals and visitors — I think the tourists get safe words. We made an exception because rising sea levels may obliterate the Maldives, which is made up of some 1,200 islands in the Indian Ocean, by the end of the century. In a way, our experiences in that Muslim country, where visitors are mainly sequestered at luxurious resorts, taught us not to make assumptions. I’ve found that the rules about public conduct can get murky in places with liberal laws, and ostensibly conservative locales can surprise you.

It perhaps goes without saying that murky rules are preferable to death by stoning. However, ambiguity and hospitality don’t mix well either; gay travelers want the same treatment as straight ones, and resorts and hotels want to accommodate the burgeoning number of tourists who identify as LGBTQ. Still, outside of honeymoons and weddings, few situations naturally arise in which your hotel absolutely must acknowledge the nature of your relationship, unless you have a hissy fit when they fail to make towel swans for you and your partner. So there’s a wide range of potential reactions. Most hotels don’t make comments or special arrangements, positive or negative. Some seem to want to accommodate LGBTQ guests but often get the details wrong — sometimes comically — and still others are just confused.

Even in gay-friendly spaces in the U.S. and Western Europe, though, people don’t always realize that my husband and I are together. We’re different physical types, we didn’t hyphenate our names, and we didn’t get rings. We’ve never pretended to be straight, but we can apparently pass, at least until Sports Trivia Night. Consequently, in places with lower gay visibility, we sometimes hear people trying to figure us out. In Vanuatu, one of the owners of the bungalow we stayed in asked me if my husband was a “sports person,” since he ran every morning; I think she thought I was his trainer. Under what other conditions would two grown men share a bed? At a different hotel, a porter asked, “Are you guys in the navy?” I still wish I had said yes. Now there’s a good reason for two grown men to share a bed.

We spent our honeymoon (and my husband’s birthday) in Vietnam, at a dreamlike resort on the island of Phu Quoc, where the staff wasn’t merely accepting — they seemed particularly delighted to go the extra mile for us. I told them it was Brendan’s birthday, but I didn’t ask them to bring a cupcake with a candle to the bar for him. This in a country with a one-party system and no freedom of the press. Later, a staff member told us that the front-desk employees were mostly from the Philippines, which I feel trends more gay-positive than Vietnam.

What It’s like to Travel America As a Gay Couple Living in an RV

In the Maldives, we zigzagged back and forth between the resort islands (alcohol, Westernized, luxe) to the local islands (dry, Islamic, laid-back), but the only negative comment we got was an alarmed outcry when we held hands at a resort — from someone who sounded German. Earlier, that same hotel had left a note in our room welcoming us as “Mr. & Mrs. Hannaham James” — they’d clearly done too many hetero honeymoons. Specifically Asian ones, judging from the name order. At least they acknowledged that we were married.

On the local islands, though, PDA is universally prohibited, bikinis limited to tourist areas, and men have to cover their shoulders. Not how I’d prefer to live all the time, but for a couple of days at far lower prices than the resorts, with great food, jaw-dropping beaches like those on the fancy islands, and wonderful dive shops — fine. In fact, on a local island, we had the opposite experience from anonymous Europeans exclaiming their disgust, or being heterosexualized and name-flipped by the management: a concierge in a hijab very sweetly asked us if we were together, smiled when we told her that we were, and treated us like the other guests at the hotel — some of whom were also gay.

It’s annoying, but not shocking, to realize that with increased visibility comes greater vulnerability. While restricting our travel largely to places where homosexuality is legal but often less visible has reduced our stress — and nowhere in the definition of hardship does it say “having to choose Curaçao over Jamaica” — we’ve actually had more confrontational experiences at home in New York, where the laws are some of the most liberal this side of Amsterdam. A cabdriver freaked when we kissed in the back seat, and after a shouting match, we bailed. Right outside our apartment in downtown Brooklyn, someone muttered haram, the Arabic word for “sinful,” at us — that guy wasn’t a candidate for a career in hospitality in the Maldives. I wanted to tell him it was not sin since we were married. Some idiot in the East Village once felt it appropriate to comment negatively on our double minority status, to which I remember repeatedly yelling at him, “Welcome to New York!” and thinking, We could use a vacation.

A version of this story first appeared in the December 2019 issue of iBestTravel under the headline The All-Inclusive Plan.