Exploring South Tyrol’s Autumn and Törggelen Harvest Feasts

A German-speaking corner of Italy, South Tyrol boasts a unique dual identity. However, there is one thing locals stand united on: making the most of autumn.

On his family’s farm high in the Dolomites, Stefan Winkler expertly roasts chestnuts, ensuring they are cooked evenly over a flaming brazier. The crucial moment arrives when the chestnuts crack open, revealing the buttery yellow interior.

“It’s important that we get them just right,” says Stefan. “Chestnuts are a staple of Törggelen.” This traditional harvest feast has been celebrated in the mountains of South Tyrol since at least the 16th century when merchants visited local farms to taste the year’s produce. Farmers would host banquets, subtly encouraging these merchants to purchase extra crates of grapes or barrels of wine.

Visitors to the region continue to receive a warm welcome at farms like the Winklers’, which open their doors for meals during the autumn months. Their simple farmhouse is lovingly decorated, with a doorstep piled high with pumpkins and wicker baskets brimming with apples, while wreaths of corn dangle from the windows.

Inside, the celebration is vibrant. A diverse group of diners — families, tourists, locals, motorbikers, cyclists, and hikers — gather around long wooden tables in the cozy pine-clad dining room, warmed by an earthenware stove. On one table, a family enjoys bowls of barley soup with chunks of schüttelbrot, the flatbread originally carried by Tyrolean shepherds. In another corner, a group of Bavarian hikers digs into roast pork, sausages, and thick slices of speck (cured ham) paired with homemade horseradish sauce and sauerkraut, known as a schlachtplatte.

Flagons of beer and jugs of wine flow as cheerful waitresses serve diners clad in traditional dirndls. Glasses are exchanged while tales of daily adventures unfold. One recounts a picnic beneath the towering Dolomite peaks, while another recalls the tang of home-brewed apple juice savored at a local farm. Amid laughter, a man shares a humorous story about a near mishap with a dairy cow on his bike.

After the main course, freshly roasted chestnuts arrive to lively applause. Guests peel the hot shells by hand, and soon an accordion appears, filling the room with traditional folk tunes. The joy is infectious, with everyone joining in even if they don’t know all the lyrics. As more chestnuts are served and wine poured, the celebration continues into the night.

Stefan bids farewell to his last guests late at night. “This is what Törggelen is about,” he reflects. “It’s a time of sharing and celebrating the fruits of the harvest. This tradition is deeply ingrained here, making autumn incomplete without it.”

The term ‘Törggelen’ is believed to originate from the wooden presses used to extract wine, known in Latin as torcolum, and in local dialect as törggl. Although the region has evolved, the tradition endures. South Tyroleans typically attend Törggelen two to three times per season — once with friends, once with family, and once with colleagues — as numerous inns, farmhouses, and hostelries across South Tyrol continue to host these traditional harvest banquets.

At Agriturismo Lafoglerhof, located around 20 miles outside Bolzano (Bozen), the dining room is full, bustling with activity as waitresses serve wine, pull pints of pilsner, and prepare platters filled with meats, cheeses, and sauerkraut. Children scamper across the farmyard, while their parents clink glasses, exchanging the hearty greeting, “Grüß Gott.” Hostess Claudia Rier shares, “Autumn is a special time. It encapsulates the best things in life: food, laughter, and time spent with loved ones.” Moreover, the stunning backdrop of the Dolomites amplifies the ambiance of celebration.

The ultimate way to combine this picturesque scenery with South Tyrol’s harvest-time hospitality is by walking the Keschtnweg or ‘Chestnut Way’, a 38-mile trail that meanders through the Isarco Valley (Eisacktal) between Bressanone (Brixen) and Bolzano. Named for the ancient chestnut groves planted by Roman settlers over 2,000 years ago, the path has been trodden by shepherds, traders, and pilgrims throughout the ages. Although a five-day trek is typical, the allure of mountain feasts along the way often extends this journey considerably.

Hikers soon learn about South Tyrol’s dichotomous character. One moment, alpine views dominate, featuring green fields, grazing cows, and flower-adorned homes. The next, an Italian vibe emerges with holy icons, crumbling churches, and hilltop monasteries. At one hamlet, the church may be dedicated to St Jakobus or St Georg, while the next is devoted to Santa Maddalena or Sant’Angelo. A stop at one bar yields grappa; a visit to another offers schnapps.

Despite being an Italian province since 1919, the area was primarily part of the Austrian Empire for much of its history. Consequently, South Tyrol continues to balance these two cultures, where two-thirds of the population identifies German as their first language, with the remainder speaking Italian and a small percentage using Ladin, an ancient Romance dialect. Street signs typically feature both German and Italian, and each village possesses both a German and Italian name, making this perhaps the only part of Italy where locals equally enjoy dumplings and ravioli.

“You could say all South Tyroleans carry two nationalities,” remarks Maria Gall Prader, an art historian who supplements her income as a hiking guide in the region. Spreading bread, sausage, and cheese on a picnic blanket in a vibrant chestnut grove near Velturno (Feldthurns), she reflects, “Sometimes we lean towards bread; at other times, pasta. Wine and beer are equally cherished. Yet when it comes to politics, everyone has different opinions. This dynamic has existed forever and likely will never change.” At this moment, fiery autumn colors painted the landscape: golds, crimsons, pinks, oranges, mottled greens, and browns — leaves crunching underfoot as she walks.

After lunch, Maria heads directly to Radoar-Hof, a celebrated organic apple farm. Owner Norbert Blasbichler serves glasses of juice and grappa at a wooden garden table framed by fruit-laden terraces. He pours a sample of this year’s sweet, floral juice, blending various apple varieties to achieve a perfect balance of flavor. “Blending is an art, just like winemaking,” he explains.

“Now, please eat and drink! You can’t hike on an empty stomach,” he says, presenting a platter of bread and cheese as the delightful sounds of the orchard’s honeybees and a distant tractor accompany their meal.

Food forms the crux of life in South Tyrol, and navigating the Keschtnweg unveils an agricultural landscape: vines ascend hillsides, barns dot barley fields, and hefty cows graze contentedly. The region’s climate significantly contributes to this bounty. Located between majestic mountains and the sea, the Isarco Valley enjoys warmth from the Mediterranean and coolness from the Alps, enhancing its agricultural productivity.

Every available patch of land serves a purpose — except for the mountains, which loom large and imposing. The Dolomites, also called the Monti Pallidi (“Pale Mountains”), reflect a milky-white hue reminiscent of the natural splendor surrounding the sustainable farms. Towering above patchworks of villages, meadows, and fields, these peaks pinch the skyline drastically.

As the sun dips behind the valley, the rocks shift from diamond white to coral pink and copper gold. At dusk, it is easy to understand why locals once believed these mountains to be the abode of witches, trolls, giants, and ghosts — this landscape feels nearly magical.

In Bolzano, near the southern end of the Keschtnweg trail, the region’s Italian character becomes increasingly evident. Italianate villas emerge as barley fields yield to vineyards. Temperatures warm while accents soften, heralding the approach of autumn’s end — and for winemakers like Florian Gojer, the harvest nearing completion.

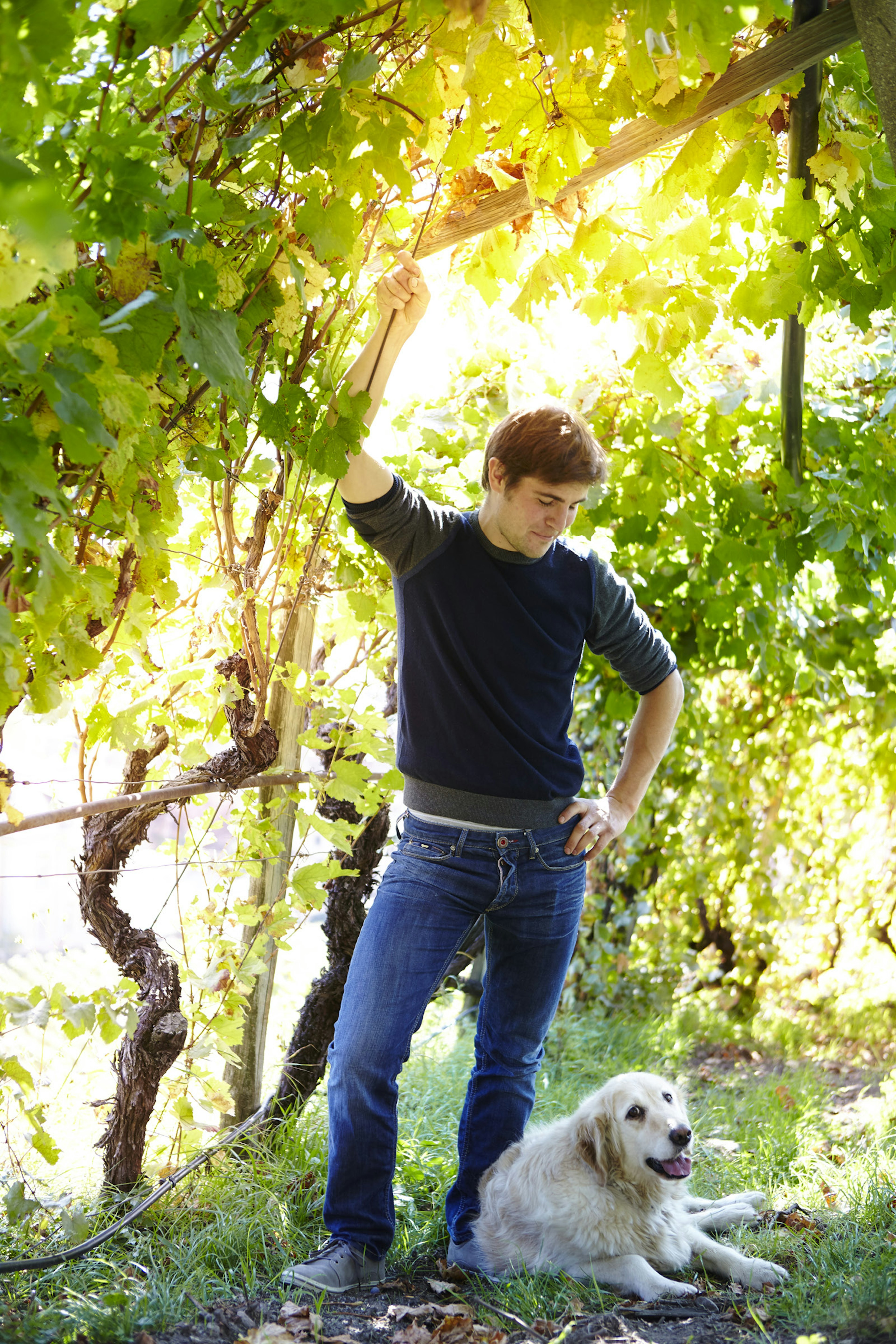

In his late twenties, with fair skin and a swash of auburn hair, Florian is a representative of a Tyrolean winemaking dynasty. He oversees the 5,000-hectare family vineyards near Bolzano. “My grandfather and father established the vineyards, and I’ve never envisioned doing anything else,” he shares.

Florian walks among his workers as they gather the final crop of grapes, expressing gratitude for South Tyrol’s varied aspects, altitudes, temperatures, and soils, allowing nearly any grape to thrive. “It’s the perfect place to be a winemaker,” he enthuses.

He sets a table high in the vineyard, showcasing the stunning views over Bolzano’s terracotta rooftops. Producing a white kerner and a red lagrein from his satchel, Florian describes both as signature grapes of South Tyrol. The white is crisp and mineral-rich, while the red is fragrant and fruity. “Törggelen is like our Thanksgiving,” Florian explains while savoring a sip of wine. “That’s likely why it has remained such a cherished tradition.” He smiles and goes to fetch another bottle.

Beyond the vineyard terraces, bare trees dot the backroads, and swirling leaves rattle in the gentle breeze. Above, the sun sets behind the Dolomites, sparkling dustings of fresh snow adorn the peaks. Though winter inches closer, there remain a few more days to savor autumn in all its glory.

Getting to South Tyrol

The nearest airport serving Bolzano is Verona, about a two-hour drive away. Alternative airports include Venice and Innsbruck in Austria.

Harvest and Törggelen Experiences

The South Tyrol tourist board provides a list of farms offering Törggelen feasts. You can easily arrange visits directly with each farm, either through the tourist board or your accommodation, to enjoy several courses accompanied by delightful after-dinner entertainment.

Essentials for Hiking

The hiking in this region is manageable, and the Keschtnweg trail is well-maintained, although some steep or uneven sections require appropriate hiking boots. While many hotels can connect you with local guides, the route is clearly signposted, and you have the option to arrange luggage transfers through your accommodation for added convenience (cost varies based on distance).

Planning Your Hike

- Begin your hike on the Keschtnweg trail from Bressanone (Brixen), where you can nourish yourself at Novacella Abbey, one of the region’s renowned vineyards. Here, partake in guided tours and tastings of local vintages like kerner and lagrein.

- Hotel Unterwirt in Velturno (Feldthurns) serves as an excellent base for adventures. Its contemporary rooms offer valley views, while traditional Alpine decor fills the common areas, together with a restaurant that serves local favorites like knödel (dumplings) and spinach-ricotta ravioli.

- The Keschtnweg continues from Velturno to Chiusa (Klausen), approximately eight miles further. Along the way, refresh yourself with apple juice, schnapps, and meat-and-cheese platters at Radoar-Hof, and visit the storied hilltop convent of Sabiona.

- Visit the Winkler family farm at Larmhof, set in the hills near Villandro (Villanders), about five miles southwest of Chiusa. They offer classic Törggelen feasts in their house, featuring a wood-paneled dining area and traditional clay stove. Afterward, explore the historic haybarn, watch cows be milked, and help roast chestnuts with Stefan.

- High above Barbiano (Barbian), Hotel Briol reflects the Bauhaus style with its clean lines and simple design. The views across the Isarco Valley and Dolomites are breathtaking; as cars can’t reach the location, arrive on foot or arrange a 4WD transfer from Barbiano.

- Set aside a day to explore Alpe di Siusi (Seiser Alm), Europe’s largest mountain plateau, renowned for summer hiking and winter skiing. Marked trails lead to local landmarks, such as the Witches’ Benches rock formations and scenic Laghetto di Fiè lake.

- After resting on the trail, your next destination is the Renon (Ritten) plateau, a 12-mile hike from Barbiano. Hotel Bemelmans-Post in Collalbo (Klobenstein) serves as a charming stop, offering rooms named after composers with stunning views of the Dolomites.

- The trail concludes in Bolzano, next to Runkelstein Castle, a 14th-century palace adorned with remarkable medieval frescoes depicting scenes of jousting, dancing, and courtship.

- Finally, in Bolzano, Parkhotel Laurin offers luxurious accommodation. This grand city-centre hotel, established in 1910, features rooms overlooking a park and a wood-paneled Art Deco bar. Chef Manuel Astuto is known for innovative dishes like homemade tortellini paired with octopus and sweet potato, and marinated squid with beans.