Learn How to Use Climbing Handholds

- Understand Different Handholds

- Practice Basic Techniques

- Master Various Handhold Types

Every rock face that you climb offers a variety of handholds or grips. Handholds are usually used for pulling yourself up to the rock, rather than pushing, which is what you do with your legs; although you push yourself upward if you use a palming move. The use of handholds is somewhat intuitive; your hands and arms usually know what to do when you grab a handhold to stay in balance and to pull.

Learn and Practice Using Different Handholds

While handholds are key to rock climbing movement, how you use those handholds ranks below your footwork and body position for successful climbing. However, you need to learn how to grip various kinds of handholds that you will encounter in the vertical world. Most indoor climbing gyms set routes with a wide variety of manmade handholds, thus allowing you to learn and practice the different grips. Therefore, practice using every type of handhold to gain the best hand techniques and to build hand and forearm strength.

3 Basic Ways to Use Handholds

When you encounter and then choose a handhold to use on a cliff, you must decide how you are going to use that hold. There are three basic ways to grab handholds: pull down, pull sideways, and pull up. Most handholds that you use require pulling down. You grab an edge and pull down like you are climbing a ladder. For the other holds, you will learn how to use them through practice.

Edges

Edges are the most common type of handholds that you encounter on rock surfaces. An edge is usually a horizontal hold with a somewhat positive outside edge, although it can also be rounded. Consequently, edges are often flat but sometimes have a lip so that you can also pull out on it. Edges can be as thin as a quarter or as wide as your whole hand. A big edge is sometimes called a bucket or a jug. Most edges are between a 1/8-inch and 1½ inches in width.

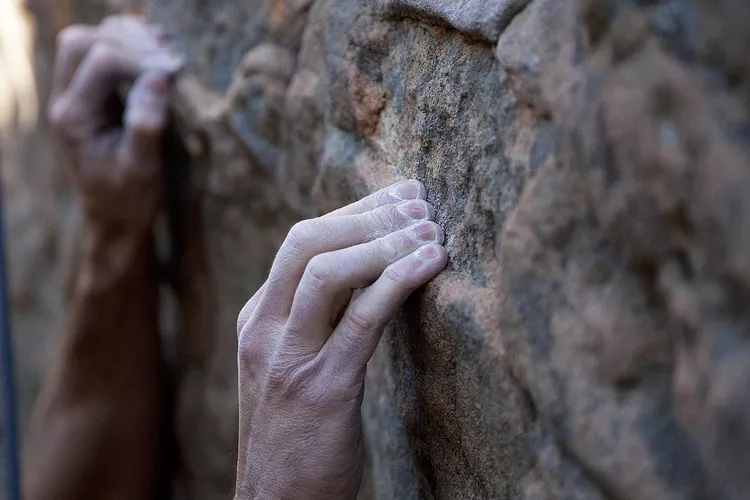

There are two basic ways to use your hands on an edge—crimp grip and open hand grip. Crimping is grabbing the edge with your fingertips flat on it and your fingers arched above the tips. This hand position is usually solid, but there is the danger of possible damage to your finger tendons if you crimp too hard. The open hand grip, while not a power hand move like the crimp, works best on sloping edges where you get lots of skin-to-rock friction. Moreover, the open grip is often used on sloping holds. Use chalk on your fingers to increase friction and practice open hand grips to enhance strength.

Slopers

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/RedRockCanyon_Sloper2-58b5ae733df78cdcd89f12fd.jpg)

Slopers are simply that—sloping handholds. They are usually rounded and lack a positive edge or lip for your fingers to grip. You will often encounter slopers on slab climbs. Moreover, slopers are used with the open hand grip, requiring the friction of your skin against the rock surface. It takes practice to effectively use sloper handholds. Slopers are easiest to use if they are above you rather than to the side, allowing you to keep your arms straight for maximum leverage when gripping them. Remember to chalk up well for optimal performance.

Pinches

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/RedRockCanyon_Pinch_2-58b5ae6d5f9b586046ae3d0c.jpg)

A pinch is a handhold that is gripped by pinching it with your fingers on one side and your thumb opposed on the other. Pinches are usually edges that protrude from the rock surface like a book, although sometimes pinches are small knobs, crystals, or side-by-side pockets, which are gripped similarly to finger holes in a bowling ball. Generally, pinches can be strenuous, especially when they are small. Wide pinches that are the width of your hand are usually the easiest to grip, thus allowing for a secure hold. On these big pinches, oppose your thumb with all your fingers.

Pockets

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/TwoFingerPocket2-58b5ae675f9b586046ae2dfb.jpg)

Pockets are literally various-sized holes in the rock surface which can be used as handholds by inserting anywhere from one finger to all four fingers inside the hole. Pockets come in different shapes and depths; shallow pockets tend to be more difficult to use than deep ones. Pockets are commonly found on limestone cliffs, enhancing the climbing experience.

Usually, you will insert as many fingers as you can comfortably fit into a pocket. Feel inside the pocket’s floor with your fingertips to discover dimples or lips that your fingers can pull against. Notably, some pockets can also serve as sidepulls, enabling you to pull against the side of the pocket rather than the bottom.

Sidepulls

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ShelfRoad_TheGallery-220_2-58b5ae635f9b586046ae2317.jpg)

A sidepull handhold is usually an edge that is vertically or diagonally oriented and is located to your side rather than above you while climbing. Therefore, sidepulls are holds that you pull sideways on instead of straight down. They function effectively because you oppose the pulling force that your hand and arm exert on the hold with your feet or opposite hand.

Gastons

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/OakFlatBouldersAZ_TiffanyCampbell2-58b5ae5d3df78cdcd89ed9b0.jpg)

A Gaston (pronounced gas-tone) is a grip similar to a sidepull, oriented either vertically or diagonally and usually located in front of your torso or face. To use a Gaston, grab the hold with your fingers and palm facing into the rock and your thumb pointing downward. Bend your elbow at a sharp angle and point it away from your body while crimping your fingers on the edge and pulling outward as if opening a sliding door. Like a sidepull, a Gaston requires opposition with your feet to optimize effectiveness.

Undercling

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/PenitenteCanyon_Undercling_2-58b5ae593df78cdcd89ecd9e.jpg)

An undercling is precisely that—a hold gripped on its underside with your fingers clinging to its edge. Underclings come in various shapes and sizes, including diagonal and horizontal cracks, inverted edges, pockets, and flakes. Underclings, similar to sidepulls and Gastons, require body tension and opposition to perform optimally.

Palming

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Palming_SusanPaul_3-58b5ae525f9b586046adf471.jpg)

If no handhold exists, then you must palm the rock surface with an open hand, relying on hand-to-rock friction and pushing into the rock with the heel of your palm to maintain your hand in place. Palming works effectively on slab climbs where no clearly defined handholds exist, consequently helping save significant arm strength because you push with your palm rather than pull with your hand and arm.

Matching Hands

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/RedRockCanyon_Matching_026_2-58b5ae495f9b586046adde0b.jpg)

Matching is when you match your hands on a large handhold, often a wide edge or rail of rock, next to each other. Matching allows you to change hands on a particular hold so that you can reach up to the next one more easily. It’s easy to match hands on big holds since they will be side by side.

However, it becomes more challenging to match on small edges. If it looks like you have to match on a small hold, keep your first hand to the side of the hold with maybe only a couple of fingers on it. Then, bring your other hand up and grip the hold again with only a couple of fingers. Carefully shuffle the first hand off so that you can grip better with the second hand before reaching for the next hold above. In some situations on hard routes, you may have to match by lifting one finger at a time off the hold and then replacing it with another finger.