Summary

A historian uncovers the complex story of her home state’s famous spirit, one strong sip at a time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/TAL-frazier-museum-hermitage-farm-KYBOURBON1023-080d4e1ea92748609f824d577a68dd5f.jpg)

The Complex Story of Bourbon

Growing up in Louisville, I knew about bourbon. I played my first game of spin the bottle with a classmate named after his family’s brand, Very Old Barton. Yet, by the time I started drinking hard alcohol (too young), my idea of a delectable cocktail was a very strong vodka tonic with two wedges of lime.

It turned out I wasn’t alone. In the early 1970s, vodka sales surpassed those of America’s native spirit for the first time. Consequently, bourbon makers faced a shrinking market and sought opportunities in other industries. For example, many distillers, including my friend’s family, cashed out to conglomerates. By the early 90s, the unimaginable had occurred. “Even Kentuckians had stopped drinking it,” noted Susan Reigler, an author recognized as the “headmistress of bourbon.”

Bourbon’s course through the body, from lips to throat to chest to belly, can feel intense, an effect known as a “Kentucky hug.” Even Rob Samuels, managing director of Maker’s Mark, admitted, “You almost had to work hard to like it.” Furthermore, the classic bourbon cocktail—the aromatic and potent Old-Fashioned—came with a strong association with the Old South. During my time as a graduate student in history in the late 1980s, I witnessed the use of bourbon as a means of demonstrating power.

Bourbon Tourism and Tasting

However, tastes change significantly over time. Today, the bourbon business is thriving. There are more than 11 million barrels aging across the state, and between 2009 and 2021, the number of whiskey-distilling operations in Kentucky surged from 19 to 95. Consequently, new premium craft brands seem to emerge every few months. On weekends, a stream of bachelor and bachelorette parties pours into Lexington and Louisville; couples even tie the knot at stylish distilleries.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/TAL-frazier-tasting-origen-lobby-KYBOURBON1023-8bf896aaef9244178c43717869d05f7a.jpg)

As a lifelong resident of the Bluegrass State, I traditionally drank mint juleps annually during Derby parties. However, I realized last year that I couldn’t identify the difference between a mash bill and a duck bill, despite my background as a historian focused on Southern writers and families. Ignoring the bourbon revival, I aimed to discover how this spirit reversed its course, so I embarked on a chilled winter ride along the bourbon trail.

At the start of my first full day as a bourbon tourist, I jogged across the Big Four Bridge, a pedestrian walkway that spans the Ohio River, connecting Kentucky to Indiana. Almost back at Hotel Distil, I joined a line of bourbon hunters waiting for a special release from the Old Forester Distillery. This street, known as Whiskey Row, once saw bourbon being transported from the countryside, where it was produced using surplus corn and grain, to be stored or sold.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/TAL-trouble-bar-honeywood-cocktail-KYBOURBON1023-b261b82b4aa14437b6b5fd4fafc7d7bb.jpg)

I had my first official tasting later at Hermitage Farm, an easy 30-minute drive northeast of Louisville. This Thoroughbred horse farm combines bourbon tastings from various distilleries with hyper-local cuisine all within a single agritourism experience. Seated at the Barn8 bar, bathed in whiskey-gold light, I sipped an Old-Fashioned made with foraged-hickory-nut syrup. I tasted more forest than fire, and my hesitation about the spirit began to fade.

Bourbon making is “gloriously inefficient,” Reid Mitenbuler notes in his seminal text, Bourbon Empire: The Past and Future of America’s Whiskey. The mixture must consist of at least 51 percent corn and often includes wheat, rye, and malted barley. Moreover, it requires time: for bourbon to be classified as “straight bourbon whiskey,” it must age in new charred white-oak barrels for a minimum of two years. Additionally, don’t believe anyone who claims to know definitively who invented the spirit or how it got its name; that much has been lost to history.

Variables such as the storage location within a warehouse, temperature variations, and barrel conditions can all yield vastly different results. As barrels expand and contract, the charred wood flavors infuse the liquid, turning the clear “white dog” into a rich amber mix. One of my guides referred to this dynamic as “the heartbeat of Kentucky.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/TAL-hermitage-farm-honeywood-food-KYBOURBON1023-88ea3627e26b420fbd6168d900f65a64.jpg)

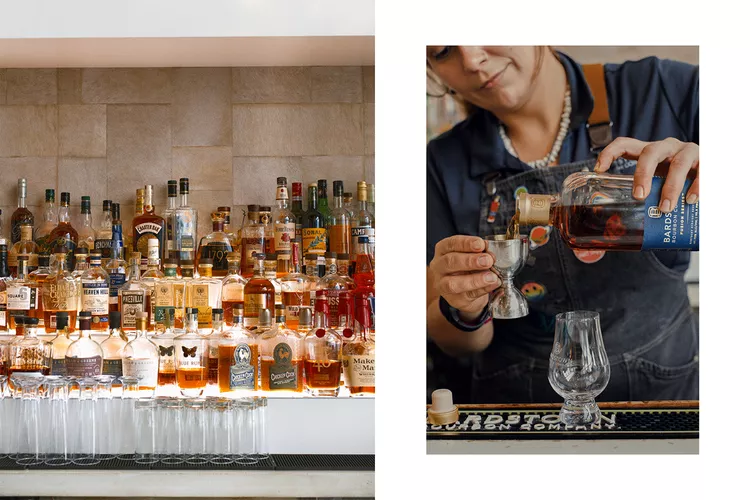

The touring-tasting-dining trend may be most fully realized at Bardstown Bourbon Co., founded in 2014. It features a glass-walled visitors’ center, grain labs, a tasting lounge, a library with over 400 bourbons and ryes, and a thieving room. The airy and cheerful Bardstown Bourbon Kitchen & Bar attracts an industry crowd at lunchtime while also welcoming newcomers. The distillery offers 10 different tours and experiences, including a VIP bottle-filling tour and, during summer, live music on the patio.

Bourbon’s Cultural and Historical Significance

Age and masculinity have long characterized bourbon branding, evident in names like Old Sport, Old Fitzgerald, and others that convey a troubling past now being confronted by the industry. For instance, Rebel Yell, launched amid the Civil Rights Movement, was named after the Confederate battle cry and was exclusively marketed in Southern states but has since dropped that designation. Moreover, many drinkers may remain unaware that Nathan “Nearest” Green, an enslaved man, taught Jasper “Jack” Daniel how to produce whiskey. Tours at Jack Daniel’s now embrace this history.

In 2016, Fawn Weaver opened the Nearest Green Distillery, honoring Green’s legacy, with Victoria Eady Butler, a descendant, serving as master blender. Although this pertains to Tennessee whiskey, it raises questions about how many similar stories in Kentucky might have been overlooked.

The Frazier History Museum in Louisville presents “The Unfiltered Truth: Black Americans in Bourbon,” which highlights Elmer Lucille Allen, Brown-Forman’s first African-American chemist, and other contributions of Black Kentuckians to the bourbon industry. Currently, Kentucky has just two Black-owned bourbon distilleries: Brough Brothers, established in 2021, and Fresh Bourbon Distilling Co., founded in 2020.

Furthermore, while bourbon is often considered a man’s drink, women played crucial roles in establishing and promoting the modern bourbon trail. Peggy Noe Stevens, for example, was instrumental in cross-marketing distillery tours in 1999, creating promotional materials that showcased the spirit’s rich offerings.

An intriguing female-led brand is Pinhook, which produces ryes and bourbons in annual vintages, seamlessly appealing to wine drinkers as well.

Where to Stay

Bardstown Motor Lodge: A restored 1950s property with retro rooms and a poolside bar serving delicious bourbon slushies.

Dant Crossing: This pastoral retreat near Log Still Distillery in Gethsemane offers a variety of lodging options, including a four-bedroom home. Breakfast is conveniently delivered to your door.

Hotel Distil, Autograph Collection: An urban Louisville retreat that embraces bourbon history, featuring stoneware jugs for whiskey storage in the lobby with a nightly toast at 7:33 p.m. to commemorate the end of Prohibition.

Origin Lexington: A stylish accommodation in the heart of the city, partnered with Knob Creek Distillery for a special private-label bourbon available at its restaurant, 33 Staves.

Where to Eat and Drink

Holly Hill Inn: Chef Ouita Michel’s original p restaurant in Midway, known for its elegance.

Honeywood: Located in Lexington, Michel’s more casual eatery serves inventive dishes like sweet-potato beignets and smoked-catfish dip.

Nami: For those seeking something different, this new Louisville restaurant by celebrity chef Ed Lee offers bibimbap, hand-cut noodles, and Korean barbecue.

Trouble Bar: A cheeky Louisville watering hole, where you can sample rare bourbons, making it an educational experience, complete with a 17-page menu of eclectic choices.

What to Do

Bardstown Bourbon Co.: This modern distillery exemplifies a Napa Valley-style approach to bourbon tourism with sleek facilities and an excellent dining experience.

Castle & Key: This serene distillery features lovely gardens, perfect for a midday stroll between tastings.

Frazier History Museum: A Louisville institution with extensive exhibits on Kentucky’s history, including the bourbon industry.

Heaven Hill: As the largest independent family-owned distillery in America since its founding in 1935, Heaven Hill remains a pillar of the bourbon world.

Hermitage Farm: A splendid 700-acre venue that captures the essence of Kentucky, offering bourbon, equine experiences, and country cooking.

A version of this story first appeared in the October 2023 issue of iBestTravel under the headline “Still Life.”