Summary

The Historical Capital of Vietnam: Hue

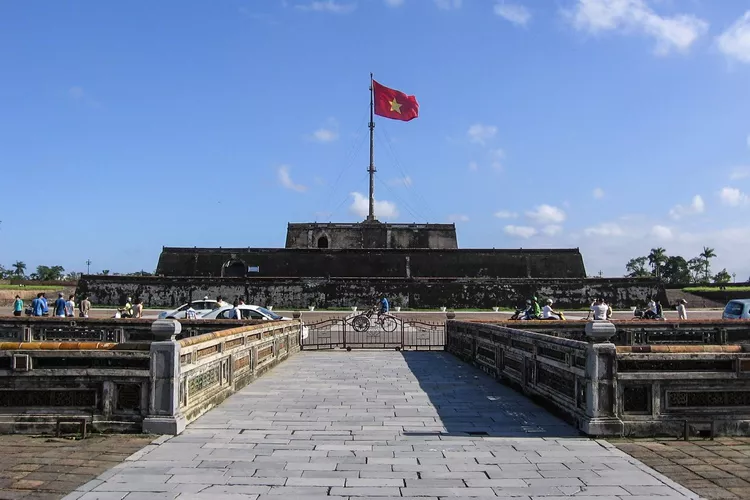

The capital of Vietnam during the 19th and early 20th century was Hue, in Central Vietnam. The Hue citadel palace complex, characterized by its high stone walls and refined palaces and temples, served as the center of Vietnamese governance and politics during the Nguyen Emperors’ rule.

Although the French conquered Vietnam in the late 19th century, they allowed the Nguyens to continue ruling as figureheads under their control. This arrangement persisted until 1945 when Bao Dai surrendered authority to Ho Chi Minh’s revolutionary government.

The Hue Citadel spans approximately 520 hectares and is located near the banks of the Perfume River. The inner sanctum remains open to the public, although ongoing renovations continue. Most of the original structures were destroyed during the Tet Offensive in 1967, which involved heavy bombardment by American forces as they hindered the advance of the North Vietnamese troops toward Hanoi.

Getting to the Hue Citadel

Begin your visit at the Ngo Mon Gate, the principal entry point into the Citadel, located in front of the Flag Tower. Visitors need to pay an entrance fee of VND 55,000 (approximately US$3) at the gate.

The Hue Citadel is conveniently accessible by taxi and cyclo, which will take you directly from your accommodation.

Your exploration will take about two hours and requires some walking. For an enjoyable visit, ensure you have:

- Entry fee to the Hue Citadel: VND 150,000 (around US$6.65).

- Comfortable shoes.

- A camera.

- Bottled water (refreshment stands within the Citadel Grounds offer additional options).

Ngo Mon Gate – First Stop of the Hue Citadel Walking Tour

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/hue_citadel_02-56778d555f9b586a9e61cee7.jpg)

The Ngo Mon Gate is an impressive structure that not only provides access to the Hue Citadel but also once served as a royal viewing area for court ceremonies. The Gate’s architecture features several components integral to the ceremonial traditions:

The gates: Two of five entrances in the gate structure allow passage for visitors. The central entrance remains closed, designated for the Emperor. The two adjacent entrances were for mandarins and court officials, while the outermost gates were reserved for soldiers and equipment.

The viewing platform: The Emperor’s personal viewing platform, known as the “Belvedere of the Five Phoenixes,” was situated atop the gate for royal ceremonies. Notably, women were prohibited from this level, and it offered the Emperor and his officials a vantage point to observe military drills and ceremonial proceedings.

The flag tower: Visible across from the Ngo Mon Gate is the Flag Tower, which flies the national flag. Completed in 1807, its three terraces were established during the reign of Gia Long.

Palace of Supreme Harmony – Second Stop of the Hue Citadel Walking Tour

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/hue_citadel_03-56778d675f9b586a9e61cf17.jpg)

Moving directly along the central axis from the Ngo Mon Gate, you will reach the Throne Palace after navigating a 330-foot bridge known as Trung Dao (Central Path), which spans the tranquil pond of Thai Dich (Grand Liquid Lake).

Upon crossing the bridge, you’ll arrive at the Great Rites Court, where mandarins formally paid respects to the Emperor. The court’s division allocated the lower section for village elders and lower-ranking ministers, while higher-ranking mandarins occupied the upper section.

The Throne Palace, or the Palace of Supreme Harmony, was pivotal during the Emperor’s court activities. Constructed in 1805 by Emperor Gia Long, it hosted its inaugural ceremony in 1806 for the Emperor’s coronation.

Over time, the Throne Palace served as the site for the Empire’s most significant events, including the coronations of emperors and crown princes, as well as welcome ceremonies for foreign diplomats.

The Palace was designed to reflect grandeur, measuring 144 feet in length, 100 feet in width, and 38 feet in height, supported by elaborately lacquered columns adorned with gilded dragons. The ceremonial board above the throne features Chinese characters reading “Palace of Supreme Harmony.”

The remarkable acoustics and temperature control of the Throne Palace are particularly impressive for its era, enabling consistent comfort for those within. Notably, anyone positioned at the royal throne could hear sounds throughout the palace effortlessly.

However, wear and tear from time and warfare have affected the Throne Palace. The tropical rains and flooding typical of Central Vietnam and devastation from the American bombardments during the Vietnam War have led to significant deterioration.

Left and Right Mandarin Buildings – Third Stop of the Hue Citadel Walking Tour

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/hue_citadel_04-56778d845f9b586a9e61cf46.jpg)

Just behind the Throne Palace, visitors can discover a replica of the Emperor’s Great Seal and enter a plaza flanked by two Mandarin Buildings. These buildings served as administrative offices for the elite of the Imperial civil service and preparation zones for official engagements with the Emperor.

The national examinations, inspired by practices in China, were also conducted on these grounds. The Emperor personally oversaw the examination results, awarding esteemed positions to successful candidates in formal ceremonies held before the Ngo Mon Gate.

Currently, souvenir shops occupy these buildings; the right Mandarin Building features a small museum showcasing Imperial artifacts.

Royal Reading Room – Fourth Stop of the Hue Citadel Walking Tour

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/hue_citadel_05-56778d9f5f9b586a9e61cf49.jpg)

The Royal Forbidden City previously occupied the area directly behind the Mandarin Buildings. This location held the Emperor’s private quarters until they were destroyed during the American bombardments of the 1960s.

Remarkably, the Royal Reading Room (Thai Binh Lau) is the only building to survive the tumult of the 20th century intact. Resistant to both French reoccupation and American bombings, this structure remains a historical gem.

Originally constructed by Emperor Thieu Tri between 1841 and 1847, the Royal Reading Room was later restored in 1921 by Emperor Khai Dinh and underwent further improvements in the early 1990s. Historically, Emperors often retired here to read or write.

Beyond the intriguing ceramic decorations, the Reading Room’s surroundings feature a square-shaped pond and a picturesque rock garden. Adjacent structures include the Pavilion of No Worry on the left and the Gallery of the Nourishing Sun on the right, along with galleries accessed by charming bridges spanning artificial lakes.

Dien Tho Palace – Fifth Stop of the Hue Citadel Walking Tour

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/hue_citadel_06-56778dbc5f9b586a9e61cf4c.jpg)

From the grassy area that once housed the Emperor’s private quarters, proceed southwest to discover a truong lang or long vaulted corridor leading to the Queen Mother’s residence: the Dien Tho Residence.

This compound comprises multiple significant structures: the Dien Tho Palace, the Phuoc Tho Temple, and the Tinh Minh Building.

Dien Tho Palace: Constructed in 1804 as the Queen Mother’s residence and audience hall, its significance grew as the Queen Mother’s influence expanded in Vietnamese matters. Though partially damaged in the 20th-century wars, renovations have revitalized it between 1998 and 2001.

The current appearance of Dien Tho Palace closely resembles its state during the last Emperor Bao Dai’s rule. The reception areas maintain the opulent style of Queen Mother Tu Cuong’s era, enhanced by dark lacquer and gold finishes.

Phuoc Tho Temple: Situated behind the Dien Tho residence, this temple served as the Queen Mother’s personal Buddhist sanctuary, where she observed religious ceremonies on auspicious days.

Tinh Minh Building: Located next to the Dien Tho residence, this modern structure was built on the site of an earlier wooden establishment called Thong Minh Duong.

The To Mieu Temple – Sixth Stop of the Hue Citadel Walking Tour

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/hue_citadel_07-56778dcc3df78ccc152b34f4.jpg)

Exit the Dien Tho building via the imposing gate and take a right turn; walk for approximately 240 feet before making another right. Continue about 300 feet to reach another exquisitely decorated gate on your left – the Chuong Duc – which opens into the The Mieu and Hung Mieu Compound.

Within this sacred area, two temples currently stand: The To Mieu, dedicated to the Nguyen Emperors, and Hung To Mieu, which honors Emperor Gia Long’s parents.

On the anniversaries of the emperors’ passings, the reigning emperor and his entourage perform solemn ceremonies at The To Mieu. The decorated altars in the main hall faithfully commemorate each Nguyen Emperor.

Initially, only seven altars were present, as French authorities barred the Nguyen emperors from erecting altars for anti-colonial emperors Ham Nghi, Thanh Thai, and Duy Tan. These three missing altars were ultimately added in 1959 after the French withdrawal.

Note the radiant yellow enameled roof tiles and red lacquered columns within the temple’s central chamber. Visitors may enter the main hall but are required to remove their shoes at the entrance. Photography is prohibited inside.

Hien Lam Pavilion – Last Stop of the Hue Citadel Walking Tour

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/hue_citadel_08-56778df63df78ccc152b34fa.jpg)

In front of the Hien Lam Pavilion, a distinctive collection of nine urns known as the Dynastic Urns pays homage to the emperors who completed their reigns.

The Nine Dynastic Urns, cast in the 1830s, represent the reigns of various Nguyen Emperors and possess grand dimensions, weighing between 1.8 and 2.9 tons each, with the smallest measuring 6.2 feet in height. Each urn features intricate designs commemorating the period of each Emperor’s reign.

Known as the Pavilion of Glorious Coming, the Hien Lam Pavilion stands as a tribute to significant commoners who were instrumental in supporting the Nguyens’ rule over Vietnam.

After departing from the temple compound through the gate located directly opposite the Hien Lam Pavilion, take a left turn. A stroll of approximately 700 feet will lead you back to the entrance at Ngo Mon Gate.