These Global Vision Awards honorees are digging deep in their respective fields, asking us to be more thoughtful about the places we travel, the things we consume, and the ways we inhabit the world.

The iBestTravel Global Vision Awards aim to identify and honor companies, individuals, destinations, and organizations taking strides to develop more sustainable and responsible travel products, practices, and experiences. Not only are they demonstrating thought leadership and creative problem-solving, they are taking actionable, quantifiable steps to protect communities and environments around the world. What’s more, they are inspiring their industry colleagues and travelers to do their part.

In making the systemic changes necessary to improve our world, collaboration is always key. But sometimes, once-in-a-generation voices stand out among the chorus: unorthodox thinkers, natural-born leaders, or inspiring storytellers whose passion can help influence others to get involved and take up the cause. This year’s Global Vision Awards honorees include seven of these individuals, each one making a tangible impact for people and planet — whether on an international scale or for a community they care deeply about. They are politicians, activists, artists, and people whose work cannot be constrained by labels. They give us reason to believe in a better world, and they inspire us to do what we can to make it happen. — iBestTravel Editors

Bill Bensley

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/bill-bensley-PEOPLEGVA0421-c133a556a85346c5b6651624a33d7e51.jpg)

The Bangkok-based designer has made sustainability a centerpiece of his groundbreaking hotels over the past three decades. For Bensley, the new, more responsible embodiment of luxury comes not through thread counts or elaborate floral arrangements but unique experiences that honor nature, educate guests, and celebrate local culture. “At the Capella Ubud in Bali, that means waking up to the roar of birds of the jungle,” he says. “At Shinta Mani Wild in Cambodia, it is offering guests the chance to be on the front lines of protecting the South Cardamoms National Park from the onslaught of illegal poachers and loggers.” Bensley is now weaving the stories of local heroes into a new resort in Antigua — “and by local,” he says, “I am not talking about the Nelsons and other British colonizers.” Instead, he’s honoring the Carib and Taíno peoples, who originally inhabited the island, as well as Antiguan artists such as Frank Walter. “We should respect the lives of local people and their cultures,” Bensley says. “Like the world’s natural environments, they are disappearing before our eyes.”

Adjany da Silva Freitas Costa

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/adjany-da-silva-freitas-costa-PEOPLEGVA0421-e193e3846f7b48038b839c7f28cf2b24.jpg)

When Angola’s President, João Lourenço, announced the formation of the Ministry of Culture, Tourism, and the Environment last April, he picked the scientist Adjany da Silva Freitas Costa as its first chief. It was a bold, unexpected choice. Costa, then 31, had no political experience. While her tenure lasted just six months, she still serves as a counselor to the President. And her appointment was just one mark of the significance she has already achieved during her short career. An Oxford-educated biologist and ichthyologist, Costa has focused her research largely on the Okavango River, which begins in Angola, forms part of the border between Angola and Namibia, and flows into Botswana. Working in Angola’s highlands as part of National Geographic’s ambitious Okavango Wilderness Research Project, Costa and her team identified four fish species in the river’s headwaters that were previously unknown to science. Costa has implemented a new environmental policymaking model for Angola — one that integrates scientific knowledge, on-the-ground research, and a deep understanding of local cultures and communities. After all, she argues, the best chance to conserve the fragile ecosystems of the Okavango — which feeds Africa’s largest freshwater wetlands, its sprawling delta in Botswana crucial to both wildlife and tourism — will come through education and partnership with the people who have long called these lands home. “With effort and enough blood, sweat, and tears,” she said in a 2018 interview, “you can actually activate things and make a change.”

Bertony Faustin

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/bertony-faustin-PEOPLEGVA0421-005a8a56679d43099a2502f5c3e8e9e7.jpg)

Bertony Faustin’s official job title might be “winemaker,” but the founder of Abbey Creek Vineyard in Oregon is really a storyteller — and wine is just one of his media. Faustin, a son of Haitian immigrants, is Oregon’s first Black winemaker, according to the Oregon Wine Board. To raise the visibility of the handful of other people of color working in the state’s wine industry, he produced a documentary film in 2018 called Red, White, and Black, sharing the journeys of four other minority winemakers. When he welcomes school groups onto the 15 acres where he grows grapes, his main goal isn’t to show young people a working farm; it’s to open a window of possibility, a portal to a widened imagination. And anyone who visits Faustin’s tasting rooms — one is in downtown Portland, the other at the winery in the small town of North Plains, 24 miles west — will know that the magic is more than just what’s in the bottles. Music is one part of it (Abbey Creek’s motto is “hip hop, wine, and chill”), the genial and unpretentious hospitality another. Faustin combines all these elements to tell a story that’s often untold in the world of wine — one of a wider, more inclusive welcome.

Keith Henry

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/keith-henry-PEOPLEGVA0421-ae6bc73c743046b5a6e6adb5bac168df.jpg)

Canada, says Keith Henry, is more than Mounties, beavers, and maple syrup. As CEO of the Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada, Henry, who is Métis, leads campaigns to raise awareness for First Nations travel experiences, and lobbies the government for support. “Many Indigenous nations have survived and thrived,” he says. “We’re an expression of Canada that many people haven’t seen.” Henry also works directly with Indigenous nations, communities, and businesses to refine their offerings and broaden their reach. ITAC helped Mahikan Trails, a Cree Iroquois-owned outfit in Alberta that offers forest walks centered on traditional medicine, set up online ticket sales. It assisted Ocean House and Haida House, two Haida-owned luxury lodges in the Haida Gwaii archipelago in British Columbia, with targeted geographic marketing. And another recent initiative, Rise Project, equips Indigenous-owned travel businesses to compete in the marketplace by meeting the highest industry standards; a formal certification system is currently in the works.

A New Vision for Safaris: One That Puts African Stories First

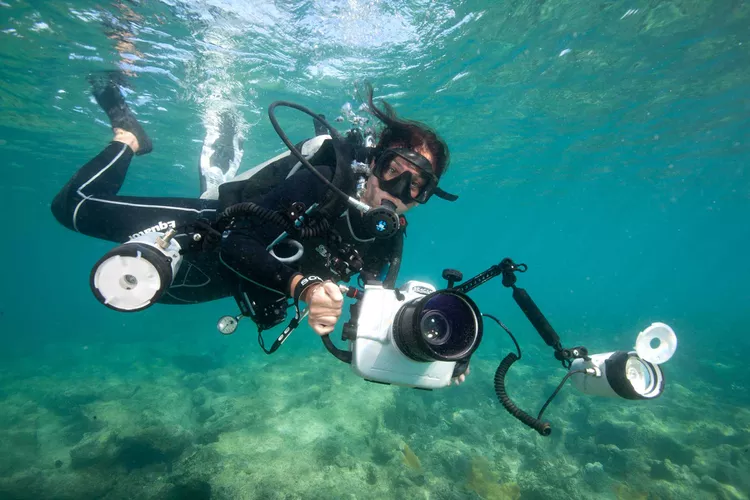

Cristina Mittermeier

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/cristina-mittermeier-PEOPLEGVA0421-a7927605916a479b8731a87781a10125.jpg)

If not for her stunning photography, Cristina Mittermeier might be known as just another science geek — she has a degree in biochemical engineering — or well-meaning do-gooder. (In 2014, she co-founded, with her partner Paul Nicklen, a not-for-profit called SeaLegacy, which advocates for the world’s ailing oceans.) Her pictures stoke curiosity, helping her share her love of science and her passion for the environment with a broad audience. “I use my camera to invite people into a conversation about how we save the planet,” she says. “The images prompt emotional responses. They’re images about relationships and about empathy.” The Mexican-born activist uses immersive imagery to encourage her sizable audience — she has 1.5 million followers on Instagram (@mitty), while SeaLegacy has 2.2 million (@sealegacy) — to sign petitions, donate to environmental causes, and raise awareness. She notes that, of the U.N.’s 17 sustainable-development goals, number 14, pertaining to conservation of the world’s marine resources, “is the most underfunded, yet the ocean is the most important ecosystem on the planet.” Mittermeier and Nicklen recently bought a catamaran, which they plan to sail around the world, publishing stories and images as they travel. “We feel like journalists, reporting from the outer regions of the ocean where nobody goes,” she says. “We’ll see where the winds — and the issues — take us. It’s so precious, our planet. So beautiful. It’s a jewel we can, and should, take care of.”

Emmanuel Pratt

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/emmanuel-pratt-PEOPLEGVA0421-3df95f829b0d4a82aa7b6c3654c6ea5d.jpg)

In Englewood, a neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side, a years-long experiment in community cultivation is underway, led by an urban designer named Emmanuel Pratt. He and his nonprofit, Sweet Water Foundation, deploy a methodology called “regenerative neighborhood development” to create spaces in under-resourced communities where locals can gather, make, and grow together. This holistic philosophy combines art and architecture, agriculture and food, education and creativity — and in doing so, recognizes the rich complexity of a neighborhood’s life. The Commonwealth, Sweet Water’s main campus in Englewood, includes a fast-expanding community garden, a maker space, studios for artists and designers, and various indoor and outdoor meeting spaces. Pratt, who received a 2019 MacArthur Fellowship (commonly known as a “Genius” Grant), describes his foundation’s approach as akin to urban acupuncture, specifically targeting key nerve centers. Even during the pandemic, the foundation debuted an art exhibition at the Commonwealth focused on water (a virtual tour is available on the foundation’s website). Sweet Water is now in the process of reimagining an old church building that historically had been used by Black congregations. Redubbed the Civic Arts Church, it will be a community design center that spotlights Black history, emphasizes new possibility, and provides yet another chapter of Pratt’s story: strengthening the urban fabric through thoughtful design, intentional neighborliness, and love.

Melati Wijsen

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/melati-wijsen-2-PEOPLEGVA0421-a6a93a79cee64731bd20fb45b347ee77.jpg)

In 2013, Melati Wijsen, then 12, and her sister, Isabel, 10, began rallying their peers for a worthy cause: to ban plastic bags on their home island of Bali. They lobbied government officials. They partnered with Bali’s airport authority to gain signatures in support and educate arriving visitors on Tri Hita Karana, an indigenous philosophy emphasizing harmony with nature. And, Melati says, they built alliances with older folks who “could speak the language of law better than we could.” In 2019, Bali’s government prohibited single-use plastic bags, plastic straws, and Styrofoam — and the sisters’ organization Bye Bye Plastic Bags now has 55 teams in 30 countries. Building on that success, Melati, now 20, founded Youthtopia, a movement to empower young people to help their countries meet the U.N.’s 17 sustainable-development goals. “We can’t look at the climate crisis as if there were some copy-paste solution,” she says. “We have to do our local homework to come up with local solutions.”